henrylaw

New member

I'm making a hardwood box which is to have a bottom of 3mm thick stuff. The sides of the box are dovetailed into one another. I need a 3mm (1/8") groove in the sides for the sheet material of the bottom to slot into.

My Stanley 13-030 plough plane is fine for the two sides whose grooves finish in a gap between the dovetails, because the pins cover up the end of the groove and I can simply plough it from end to end. But for the other two sides the groove has to stop short of the end of the timber, as otherwise it would be visible from the outside. (I hope this is clear: it would be a lot easier with a diagram!).

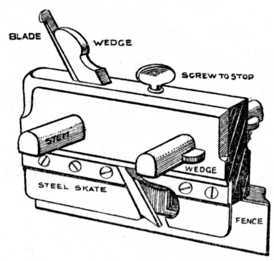

The cutter of the 13-030 is about 75mm from the front of the body, so I can't get any closer than that to the end of the groove. Is there such a thing as a "bull nose" plough plane? Would a better tool (this 13-030 is not one of Stanley's finest ...) be able to cut closer?

At present I'm finishing off the groove by using a 1/8" chisel; it's difficult and the finish isn't very good. Is there a better way?

Henry Law, Manchester, UK.

My Stanley 13-030 plough plane is fine for the two sides whose grooves finish in a gap between the dovetails, because the pins cover up the end of the groove and I can simply plough it from end to end. But for the other two sides the groove has to stop short of the end of the timber, as otherwise it would be visible from the outside. (I hope this is clear: it would be a lot easier with a diagram!).

The cutter of the 13-030 is about 75mm from the front of the body, so I can't get any closer than that to the end of the groove. Is there such a thing as a "bull nose" plough plane? Would a better tool (this 13-030 is not one of Stanley's finest ...) be able to cut closer?

At present I'm finishing off the groove by using a 1/8" chisel; it's difficult and the finish isn't very good. Is there a better way?

Henry Law, Manchester, UK.