Assembly begins!

Brace and bridge plate being glued on:

Most sopranos have two braces, one above and one below the sound hole, to stop the uke gradually folding up into its own sound hole. But the narrow waist on this shape, copied from a Dias uke of the 1890s, makes the upper bout stiff enough not to need the upper brace, so I leave it out - the lighter the better for me.

I wasn't sure whether to glue up (this was a few days ago) because the forecast humidity was on the high side, around 70%. The top expands sideways with humidity, and shrinks back when the humidity goes down. So if I glue these parts on in high humidity, as the top shrinks the brace and bridge plate will resist and the whole thing could cup or twist. But I put the heating on in the workshop and checked my home made humidity meter - two strips of veneer glued up with the grain at 90 degrees, so it bends one way if damp, the other if dry. It was bending the right way, suggesting humidity indoors of about 50 %, so glueing could happen.

The neck is glued on, making sure the centre line of the top lines up with the centre line of the neck:

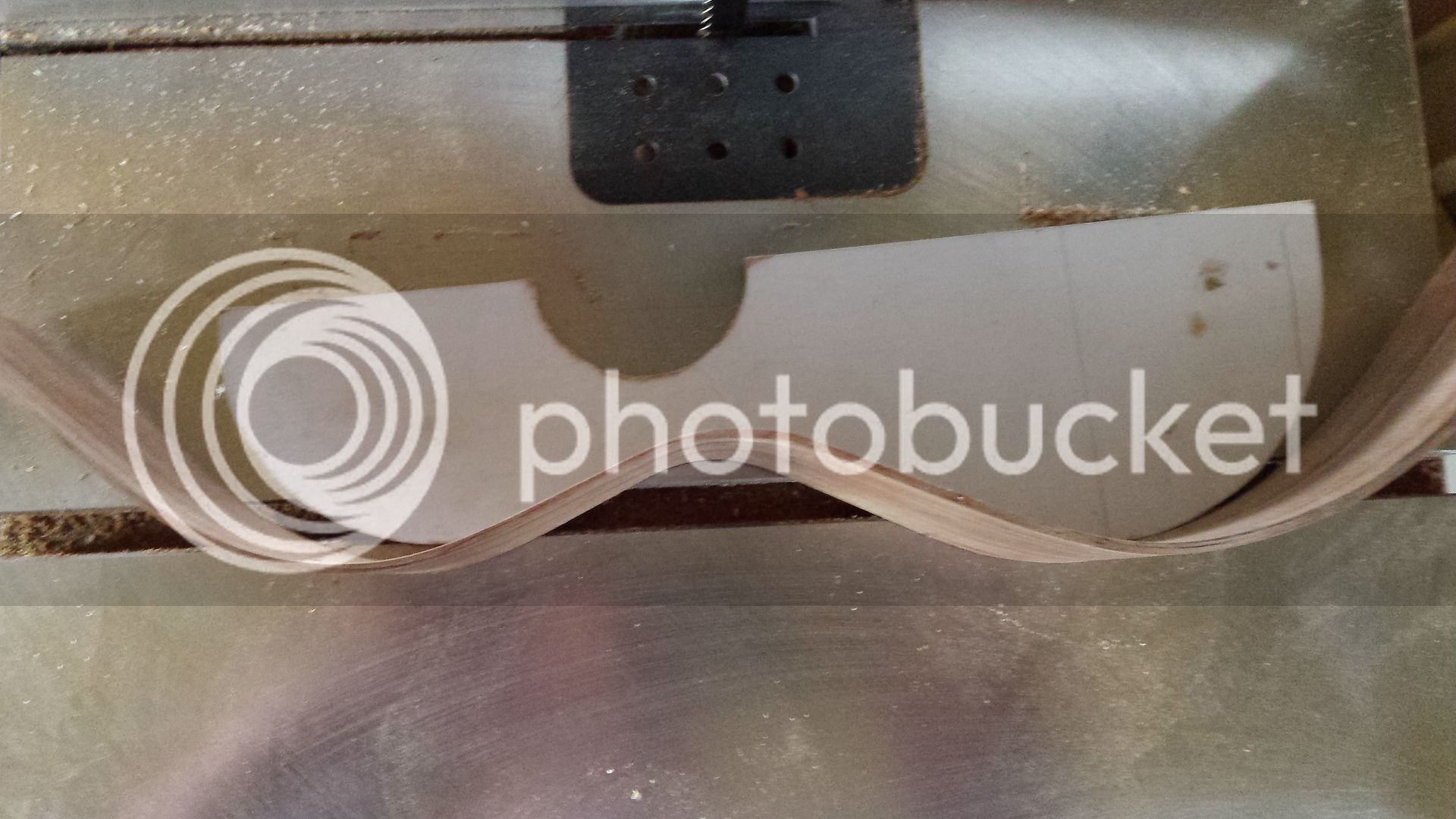

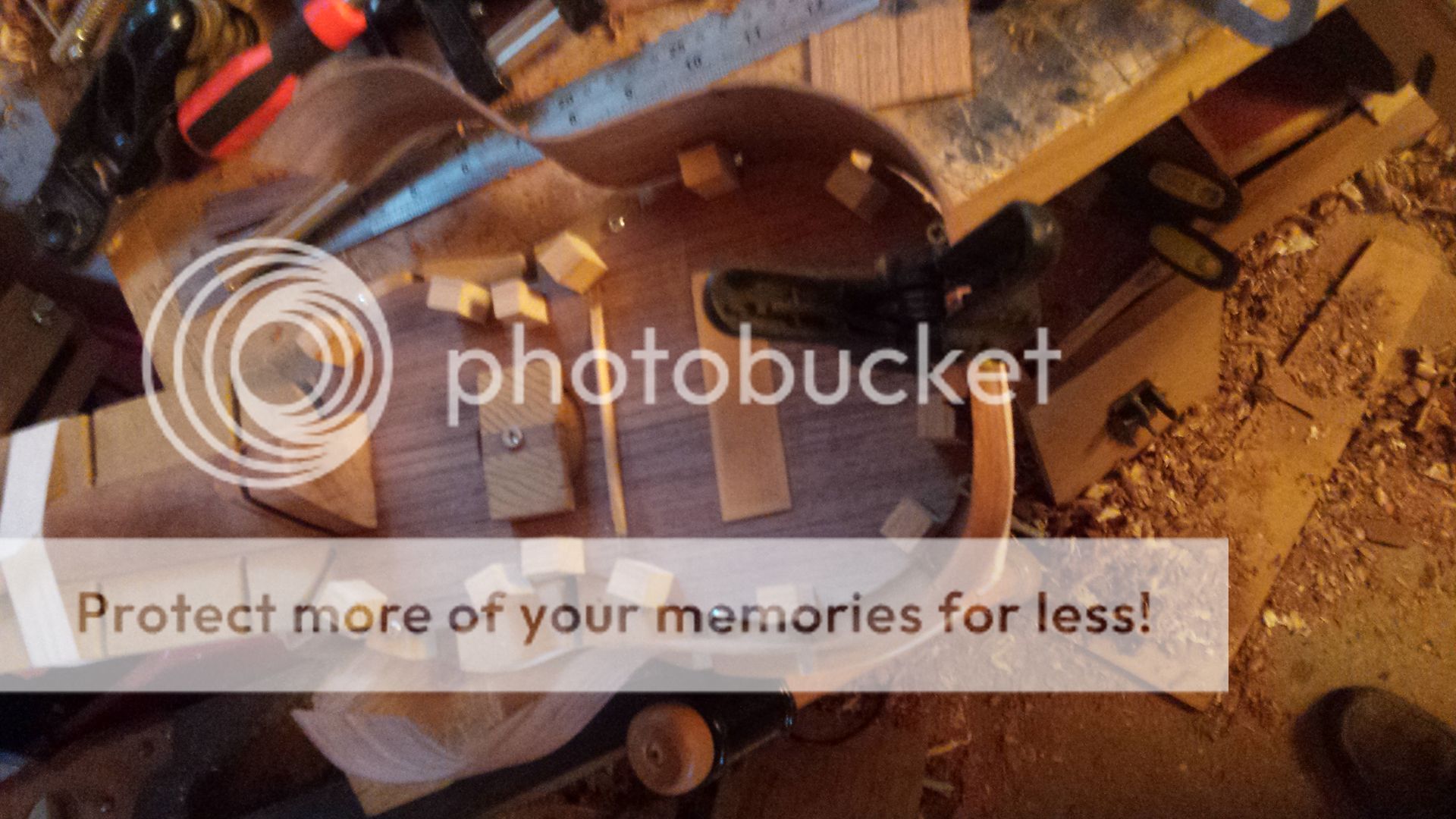

And then - loads of blocks around the edge of the shape I've drawn on my soundboard.

The reason for this is that I'm not using a mould. I will bend the sides to shape, and then trim them until they fit within the blocks. If I do this right, the blocks will make sure the body shape remains correct. Once the uke is complete I trim off the overhang together with the blocks.

As previously mentioned, I often use superglue for these block. But the Blackwood is very porous, as I discovered when I damped it with White Spirit to check the likely effect under finish, so superglue would wick through. Thus all my glueing will be done with hot hide glue. This has the reputation of being tricky, but I find it very easy to use. It has some big advantages, and we'll see one in particular when the back goes on (or maybe even earlier).

Now I attach the whole assembly to my building board, which is just a thick slab of flat MDF cut a bit bigger, and with slots for the string (yes, string might be involved).

The board keeps the top flat, and the neck in the right position, and I build up from there. To ensure the top stays flat I put a few screws around its edge so that their heads hold the top down, and screw a block across the sound hole to keep it flat there. Note to self - remove that block before gluing on the back!

And the board is used to set in my desired neck angle. This is ludicrously easy to work out, without any reference to angles at all. It goes like this:

I want the top of my saddle to be about 10mm above the top. The fretboard is 3mm thick, plus about 0.5mm for frets, so I need an extra 6.5 mm. To get 2.5mm string height over the 12th fret I need 5mm above the fretboard plane at the saddle, i.e. twice the 12th fret height, so that leave me short 1.5mm.

But the neck can be envisaged as a see saw, with the 12th fret as its mid-point. So if I need 1.5mm more at the saddle, I need -1.5mm at the nut (or zero fret in my case). I can get that by putting a 1.5mm spacer under the neck at the zero fret position and then taping down the neck.

This is such a small spacer that I didn't bother adjusting the angle at which I glued the neck on to the top. But if I'd needed a big spacer I'd have attached the top to the neck at an appropriate angle (put spacer under neck, plane top of the neck block portion until it lies flat on the board, then cut down from that to the thickness of the top).

And here it all is, locked in the right place. So long as I keep it on the board, my neck angle and alignment of neck with body will remain unchanged, even if I build the body in a completely cack-handed fashion.

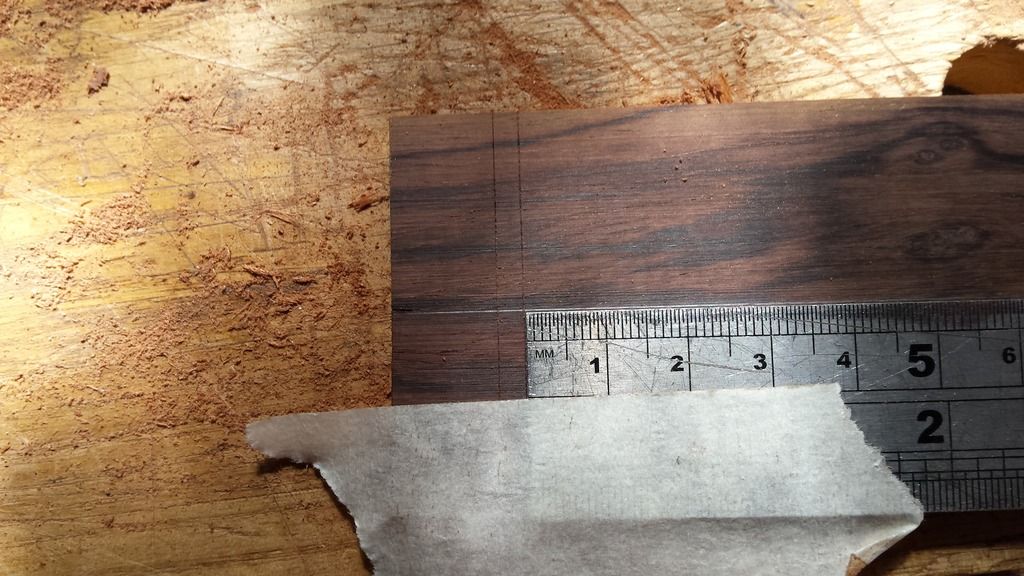

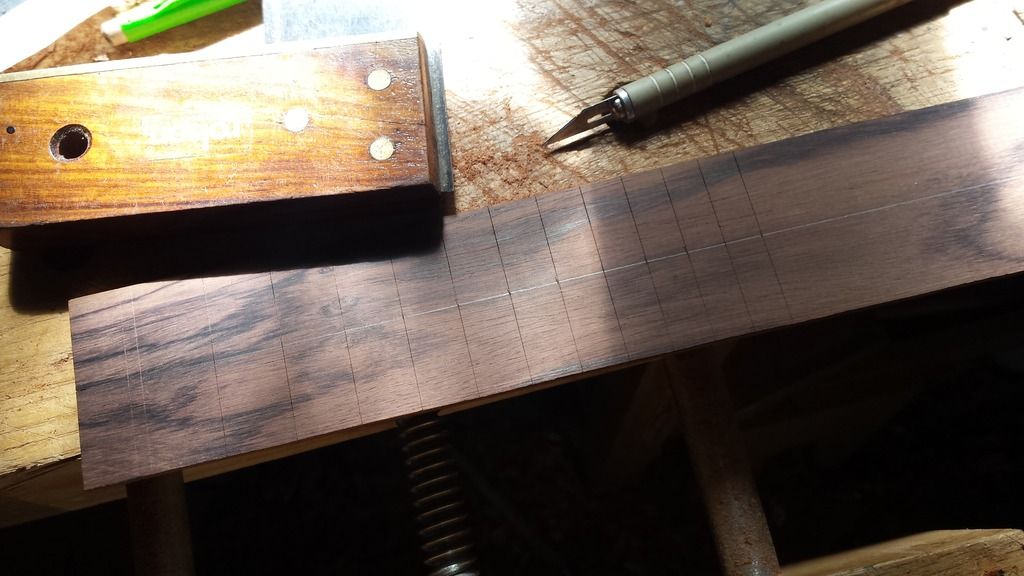

So, on to side bending. But the sides are still too thick, so some final thicknessing first (no pics of that, it's the same as thicknessing the top).