transatlantic":o8ocpbp5 said:

I didn't really have anything in mind, it's just that when I see a table with very thin legs, I wonder how the rails are joined, as there is very little space for the tenons. I know that shaker tables often get around it by having very thin tenons, but it doesn't look very strong. But then I guess it's a fine table - it shouldn't need to be strong.

I regularly make these, or items like this. The leg dimensions at the top are pretty critical, I normally aim for 32mm x 32mm, and you can get away with 30mm x 30mm, but if you try and go smaller you're skating on thin ice in terms of joint integrity. It helps if the tenons are very wide and almost the full width of the aprons. Incidentally, this side table is perfectly capable of supporting a large man standing or sitting on it, it's got all the integrity it needs for a 200+ year life expectancy.

Actually this thread also illustrates the limitations of Domino joinery. You'd think a Domino would allow you bang out Shaker style side tables in double quick time, in reality to do a good job pretty much every joint in this project needs to be individually tailored. Another joint worth reflecting on is how you would connect the two rails running horizontally above and below the drawer into the legs?

I don't have a side table on the go at the moment, but I am currently building something fairly similar,

On this the legs are about 40mm x 40mm and the side and back aprons are pretty wide at about 105mm, so it's plenty big enough to use Domino joinery for these components,

But, as with the Shaker Side Table, the two rails that run across the front need very different joinery,

The bottom rail has twin tusk tenons,

And the top rail is dovetailed into the legs,

I'm about to start making the panelled door, and that won't be suitable for Domino construction either because a decent quality job with this scale components demands

haunched M&T's, and a Domino can't do haunches.

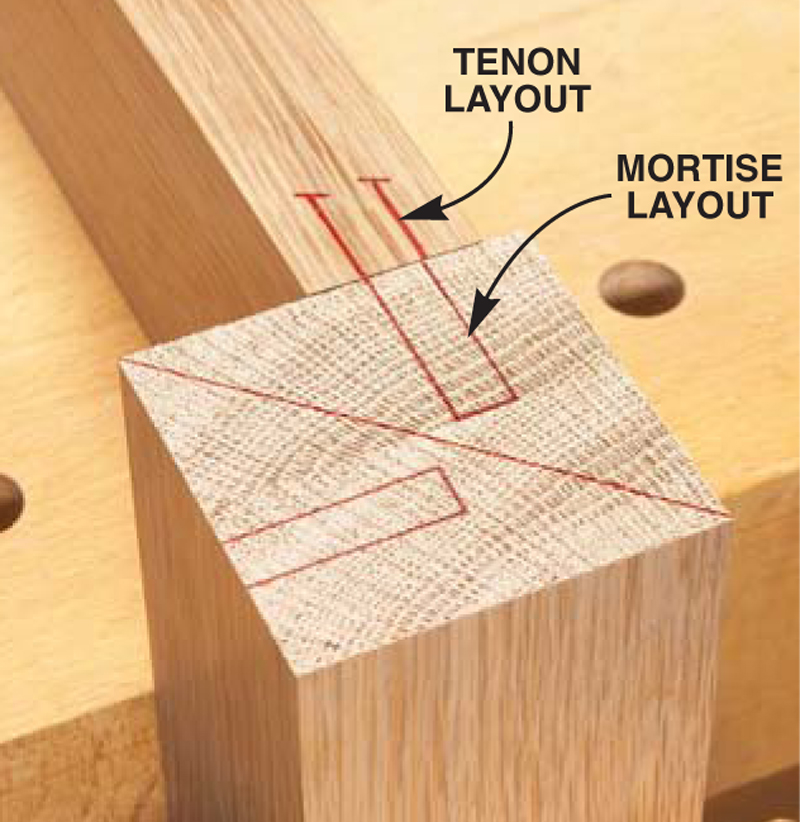

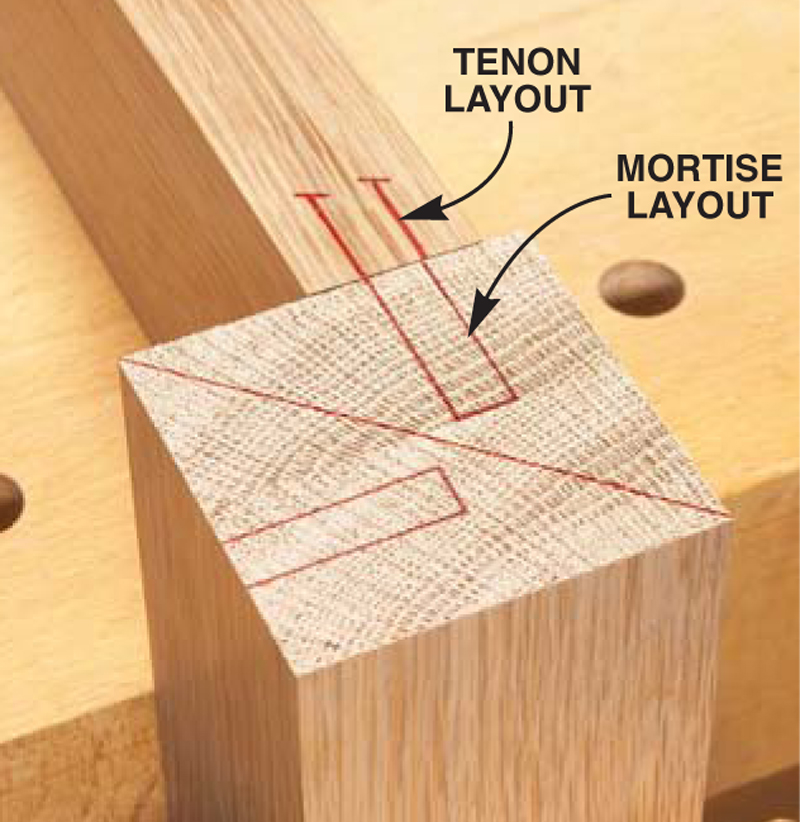

I suspect a large part of the joinery problems faced by woodworking newcomers is down to the fact that they tend to learn from books and videos that teach joinery in abstract isolation, rather than in the context of real world projects. If instead learning was project based it would be easier to grasp that joinery like dovetailed rails or twin tusk tenons is used over and over again in practical furniture making. Another important learning is that it's often useful to draw out your joinery life size or twice life size in plan and elevation before you begin, even after over thirty years of furniture making I still do this and it's never time wasted.