Back in the 19th century, there were basically two grades of steel used for edge tools, 'cementation steel' (aka 'shear steel') and 'cast steel', The first was made by taking wrought iron bars (in other words, very nearly pure iron) and packing them in containers with charcoal, then heating them at something like 1000 centigrade for about a week. This caused the carbon in the charcoal to combine with the iron to produce something called 'blister steel', which was then cooled, broken into pieces, piled into bundles and forge-welded into 'shear steel' under a tilt hammer. The result was what we would now call 'carbon steel' - iron with about 1% of carbon in it, which has the capacity to be forged into useful shapes like sheep-shear blades and then hardened and tempered to the point that it'll take a good cutting edge and hold it. The problem was that the distribution of carbon was not very even, which made the tools a bit variable. This problem was solved in 1740 by a clockmaker, Benjamin Huntsman, who wanted a more consistent steel for his clock springs; he took the blister steel, broke it into small pieces, and melted it in a small pot known as a crucible. The resulting molten steel was cast into small ingots, which could then be subsequently forged and heat treated just like shear steel, but with more consistent results. It became known as 'crucible steel' or 'cast steel' - the latter term often being stamped onto edge tools made of it. There are still a lot of vintage tools about (especially those made before about 1900) made of this steel, it's easily sharpened to a very fine edge (some people say it takes the sharpest edge of any toolmaking steel), and holds it reasonably well in most woodworking circumstances.

As technology advanced, people started to experiment with metallurgy, and the next useful edge-tool steel which cane to be widely used was what we now call 'O1'; it started to become common around 1900. It sharpens easily, takes an edge that some feel is not quite as good as 'straight' carbon 'cast steel', but more than good enough for most circumstances, and holds it well enough for most people. In the 20th century, a couple of other steel grades came to be used; for all intents and purposes, they are about the equal of O1. You sometimes see old tools marked with such designations as 'Tungsten Vanadium' and 'Chrome Vanadium' - these are matallurgically meaningless terms (O1 contains all three elements in small proportions), and are just marketing really. The tools are in all probability perfectly sound, though.

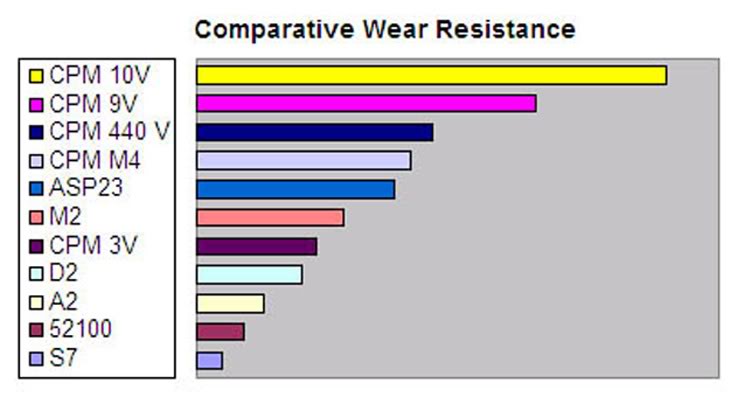

Very late in the 20th century, a specialist hand-plane maker called Karl Holtey started experimenting with available tool steels. (I should perhaps mention that there are now literally thousands of grades of 'steel', of which several hundred are 'tool steels'. Not all are suitable for making edge tools, though.) He was looking for a blade steel thar suited his planes, which were aimed at the specialist woodworkers who worked very demanding, hard, abrasive timbers. His first commercial release was a steel designated A2, which has been enthusiastically taken up by several manufacturers. It has the reputation of holding it's edge longer than cast steel or O1, but being a bit more difficult to sharpen, and being prone to chip at the edge unless bevel angles are kept a bit higher than is normal with cast steel and O1. It is also said not to take such a shap edge as O1. Later, Holtey used a powder metallurgy steel called S53, which takes an even longer-lasting edge, but needs diamond stones to sharpen it - this one has not seen such universal use.

Another steel that has crept into specialist usage fairly recently is D2, which has the reputation for holding an edge better than most edge-tool steels. It is however, harder to sharpen, responding only to diamond and ceramic stones.

Lee Valley (Veritas) in Canada have within the last couple of years released a powder metallurgy steel they designate 'PMV-11', which some people report sharpens as easily as O1, but has much better edge holding characteristics. (Others have been less positive, so the jury remains 'a bit out' so far. Time will tell as people get used to it.)

Something that has started to become more common is the cryogenic treatment of steels during hardening and tempering. Some people have reported quite positive benefits - prolonged edge life, with no detriment to sharpening ability. Whether this becomes common or remains a specialist niche remains to be seen.

There probably isn't too much point in worrying about the 'fancy' steels unless you do a lot of work in very hard, abrasive timbers. The irons supplied in most decent planes, and the blades on decent edge tools new or vintage will answer perfectly well in about 95% of circumstances, and will respond to just about any commonly available sharpening medium.

That - without getting into the complexities of steel metallurgy - is probably far more than most woodworkers really need to know. The best bet is just to get used to the foibles of the tools you happen to own, and keep them happy in their work. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, that approach will 'get you there'.