AES

Established Member

Part One

A while back Robbo 3, esteemed member of this fine congregation, PM'd me asking me to write something on files & filing. He'd noticed that I'd pontificated on this subject on the Forum before.

I was lucky enough to serve a "proper" engineering apprenticeship which started early 1961 (IMO "proper" means a good mix of practical - "workshops" - and theoretical - "schools" work), and like many others serving apprenticeships at the time, the initial practical part included quite a lot of basic bench work such as precision filing and hack sawing to quite fine limits (+/_ 0.001 in old money - i.e. a thou). This is/was called "fitting" in old terminology.

I've noticed that several other members here clearly also have good knowledge of the subject, but Robbo felt that some basics would be useful to members who perhaps have not had the "benefits" of such an apprenticeship (I wish I had had more appreciation of the in-depth treatment of these matters at the time - I just wanted to "get on with it" and start work with real aeroplanes - foolish boy that I was/am)! So I agreed to have a bash at writing up some basics which I hope members will find useful.

I also hope the following won't bore (or disagree too much with!) info that those already in the know have learnt in their own various past lives. And although it's long - very long actually - I've tried to make this a useful, practical guide for those whose main interest is woodworking but who need to do a bit of metal bashing now and then.

In the main I'll be dealing here with the common or garden "standard" metal work files and only talk about specials as the need arises.

Although they're as common as most other hand tools (more so than many?), files should be treated with respect, because they're really quite clever tools, and, in skilled hands, very capable tools too.

They're made of specially heat-treated high carbon steel (either full-cycle heat-treated, or case-hardened), and are therefore pretty hard (by most standards they're very hard). They have to be hard to allow them to happily cut just about any other metal of just about any other type or grade they're likely to come across.

But with this hardness comes a disadvantage - being hard means they're also quite brittle, which means it's quite easy to accidentally chip a cutting edge (a "tooth") - especially if allowing one file to bang against another.

Files are cutting tools, but unlike most other cutting tools, they have many cutting edges ("teeth"), as opposed to a chisel's or a plane's single cutting edge, or a router cutter's perhaps 4 cutting edges (max). But despite the many teeth, to work properly, all of the file's cutting edges need to be "all present and correct". To make it worse, being so hard, once damaged/blunted, the teeth are, for all practical purposes, impossible to re-sharpen.

So just as you wouldn't chuck a nicely sharpened chisel or a router cutter into your toolbox any old how, neither should your chuck files around - as above, be especially careful not to let files bang against each other.

These days files aren't exactly cheap (good ones aren't anyway), so I'll give a couple of ideas about safe storage further into this piece.

But all this means that if you value your tools at all, files should not be used to open paint tins, stir the contents thereof, nor for any other "gash jobs" that may come to mind - not even with a "rubbish file" from car boot sales and the like. And certainly not " 'cos it's only a file"!

So what are files for really?

Simply, files allow you to re-size, clean up, and/or re-shape pieces of metal of just about any type. And yes, I include all types of "normal" steel (including mild, stainless, spring, and silver steels); bronze; brass; copper; aluminium of all grades; nickel silver; cast and wrought iron; and even lead and solder, right on up to fancy stuff like titanium - not to mention many non-metals such as plastics of just about all types, bone, and, would you believe, wood too!

What's more, files allow you to remove material accurately, and to within fine limits - once you've acquired the necessary skill of hand!

I'll look at what acquiring that skill really means further on, but for now, jobs that might crop up in the shop and for which a file is the tool (unless you have metalworking machine tools such as lathe, mill, etc) can include:

:arrow: Removing points of screws & pins showing through visible surfaces of the work (wrong length chosen/correct size not in stock at the time!)

:arrow: Maintaining screw drivers (single slot type mainly, but a little re-work is also possible with Pozidrive & Phillips screwdrivers)

:arrow: Sharpening spade/flat bits; auger bits; Forstner bits; lip & spur bits; etc

:arrow: Sharpening various types of saw

:arrow: Removal of moulding "flash" from items with handles, etc, moulded either in plastic or die cast in metal

:arrow: General de-burring

:arrow: Making a router mounting plate (for a router table/stand)

:arrow: "Making" an adaptor to allow modern bits such as Torx to be fitted to old-fashioned tools like Yankee-type screwdrivers

:arrow: Unless there's a lot of "grinding" to do (for which I use a small circular stone in a Dremel tool with a special jig,) I also use a file for touching up the blades on garden tools such as a (rotary) lawn mower blade, shears, secateurs, etc. This is quick and easy, and is especially good for removing the burr/wire edge from the back of such blades

:arrow: General refurbishment, repair, and upgrade of tools and machinery

So files are pretty flexible tools in terms of what they can do and there are many other tasks we could add to that list.

Later on I'll look at some of the above tasks in detail, but first let's have a look at basic metalworking file types:

According to Wikipedia there's no internationally-agreed standard for the naming and classifying of files, but there are some terms which seem to be generally accepted in "general engineering English". But caution please, there are differences between US and UK usage, as well as differing usages and names within different trades on both sides of the pond. The following is what I learnt, and seems to line up pretty well with what I've heard others talking about. But as I've marked below, there are differences, particularly between US and UK terminology when defining file cuts/coarseness:

:arrow: LENGTH: Measured from the "toe" (opposite end to the handle) to the start of the handle (or where the handle is to be affixed - i.e. not including the handle itself, nor the softer, non-cutting and usually roughly triangular end called the "tang"). It seems that even in "mainland Europe", this measurement is in inches. Typically available off the shelf lengths are from 4 inches up to about 12 inches, in 2 inch steps, though I think there are some files available up to about 14, 16, or even 18 inches, and a few 3 inch files can be found too. Personally I find that some 4 and 6 inch files, plus some 8 and 10 inch files cover just about all I need for "standard" files. I have one 12 inch file, but then the work I do isn't normally all that big.

:arrow: "SHAPE" (CROSS-SECTION): The main shapes are flat, round, half-round, triangular, knife-edge, and square. These main shapes may also vary according to "sub-shape", meaning that for example a file can be parallel in both plan and in side views; or parallel in plan view but tapered in side view; or tapered in both plan and side views. And the taper can end either in a blunt-ish end or in a pretty sharp point.

Typical aspect ratios (length to width ratio) are around 10:1 for flat and half round files (i.e. a "standard" 10 inches long flat or half round file will be about 1 inch wide), with round, square, triangular files being about 20:1. Some "less standard" flat files have a much narrower length/width profile and these are called "pillar files". These are handy for getting into confined areas and I find having a couple of these useful but by no means essential.

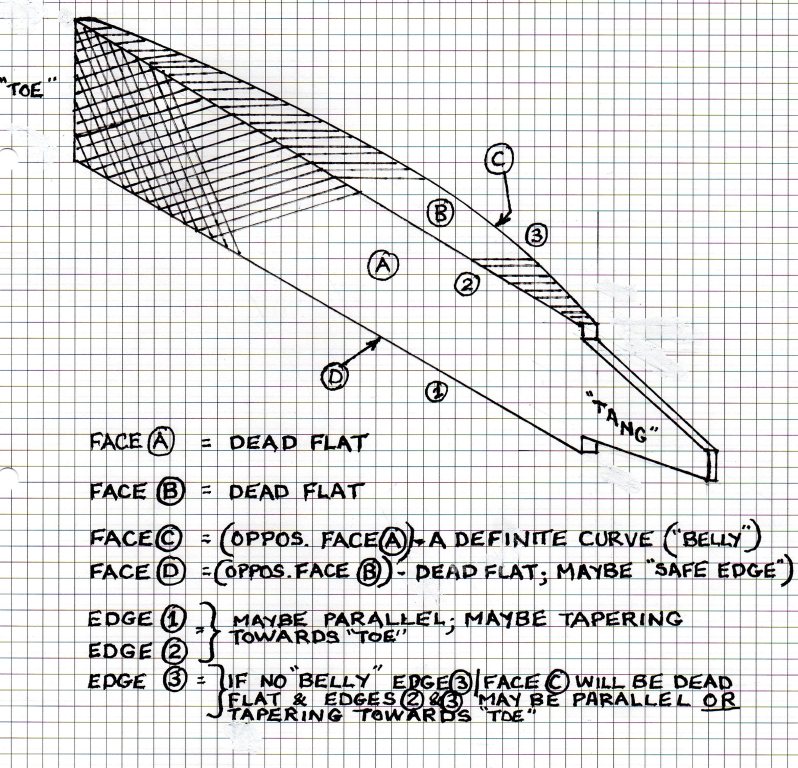

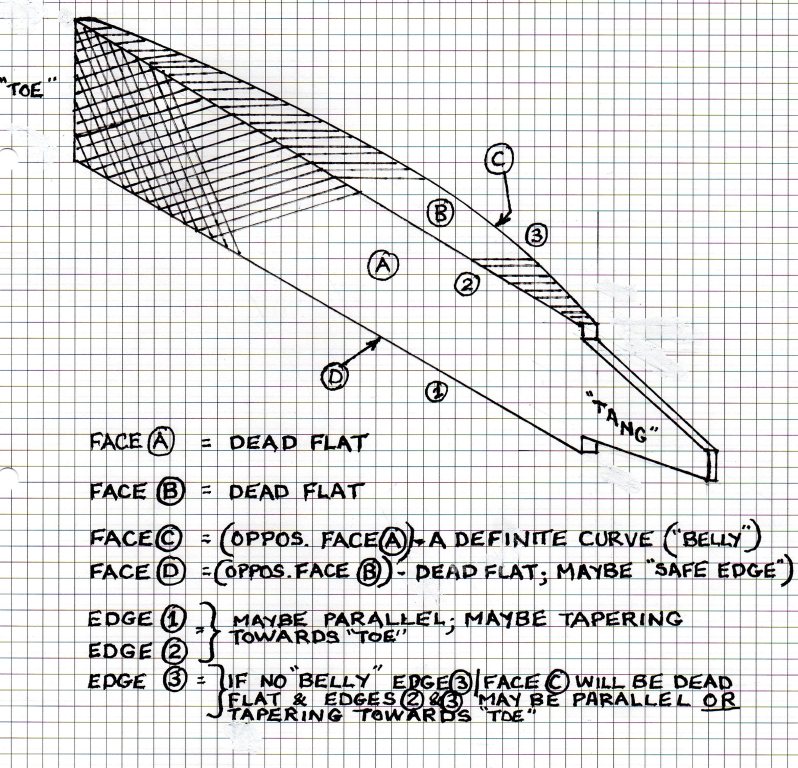

In addition, some (but by no means all) flat files have a "belly" on one side, with one face being absolutely flat but the opposite face having a marked thickening in the centre of the cutting face (see sketch below, which I've deliberately exaggerated to show this feature). BTW, at the end of this piece I've given a few references which I found very useful. However, Reference 3, while giving generally excellent descriptions, does call the general body of the file a "belly", but that doesn't seem to refer to what I've shown in the sketch. I can't really say what is "right" or "wrong", but I was definitely taught what I've drawn below:

I find this bellied type of file very helpful for fast metal clearing, but from comments I've seen here and elsewhere, it seems bellies are now not so common on off the shelf "standard" flat files as they used to be.

:arrow: "CUT": This is where most confusion seems to arise.

It all starts simply enough, running thus (from coarsest to smoothest); mill or rough (mainly USA?); coarse (mainly UK?); middle cut (mainly USA?); ******* (both UK & USA); second cut (both UK & USA); smooth (both UK & USA); Xand dead smooth (both UK & USA). Not all of these cuts are freely available off the shelf, but this is not so important as in practice I think 3 cuts (say a mill, or a coarse, or a *******; then a second cut; and finally a smooth or dead smooth) will suffice for 99% of jobs. In fact I refer to my own files in my own "in-house terminology" as just coarse, medium, and smooth.

But as we'll see later, the coarseness of the cut can anyway be temporarily modified for specific purposes, and when we get to needle files we'll see different coarseness classifications.

The basic thing remember though is all these terms refer to the number of teeth per inch set out along the cutting face/s, and you'll soon get used to selecting the "right" cut to do a particular job efficiently, simply choosing by one of your files by eye, and by the cutting feeling you get when first starting the job.

I thought the picture below, which I copied from Wikipedia, was pretty good. If only all files were marked like that, it would make life much easier!

So far so good, but now it gets more confusing (and we're still only talking about "general metal work files" and not yet about specials)!

Most files have one set of teeth cut at an angle of about 25 to 30 degrees across a face, each row of teeth being parallel to the previous row, but with a second or double cut of parallel teeth superimposed on the first cut at a different angle (usually about 55 degrees), and usually somewhat shallower than the first set of teeth. This creates the common diamond pattern. Such files are called "cross-cut" or "double-cut" files (not "second cut" files, please note)! The purpose of that cross cut is to provide chip breakers. This increases efficiency and reduces the effort needed to remove the maximum material with each stroke of the file by ensuring that chips and burrs are cleared away from the teeth as quickly as possible.

OTOH, files with only one set of teeth cut into them are called "single-cut" files - "eezy-peezy rules OK"!

But do note, not all of the second ("cross-cut") teeth of some manufacturer's files are straight line tooth cuts at all - some are cut in a curved formation, doing away with the more common diamond pattern and creating a sort of "lazy S" pattern instead.

The next potential confusion arises from the fact that while, for example, a coarse grade file is considered by just about everyone to be pretty coarse (just as you'd expect). But for example, a 6 inch file classified as a coarse cut file will be a lot finer than, say, a 12 inch coarse cut file. This is because the manufacturer makes the depth and spacing of the rows of teeth of whatever cut being made proportional to the length of the file. Obvious really, because it's generally reckoned that you'll use big/long files on big work pieces, and little/short files on small jobs!

I hope the pictures make all these points a bit clearer.

Not all files have teeth cut into all faces. Some files come with one or even two faces without any teeth. These are called "safe edges" and make it easier to file one area of a job without an adjacent face of the file accidentally filing into an area of the job that you do not want to touch. BTW, one good way to judge the quality of a file is by its safe edges/s (if any) - cheaper files tend to leave the edges of the teeth "hanging over" onto the adjoining safe edge (see exaggerated sketch below), while better quality files have the safe edge/s ground off completely smooth after tooth cutting, giving truly safe edge/s. For special use you can of course grind your own full or partial safe edge/s by use of the off hand bench grinder, and you can touch up poorly-made files to improve safe edges in the same way.

Finally in the matter of cuts, half round and round files are made with a series of slightly overlapping flat cuts. Cheaper files have less of these cuts than those from the better manufacturers, so clearly the cheaper files do not follow the ideal circular or semi-circular profiles as well as the more expensive files. And cheaper half round files have "blunt-ish" sides (where the curved upper segment meets the flat under part). More expensive files which have nice sharp edges with teeth all the way down the curves, terminating in a sharp edge each side.

:arrow: And now, HANDLES: Some "standard" metal work files can be bought with handles permanently attached to the file (wooden or moulded plastic). Others come without handles, leaving the buyer to choose his own.

In the latter case, we're back to the above-mentioned "tang" again. In relation to the rest of the file, the tang is deliberately left pretty soft, and generally speaking, manufacturers are not all that careful about the exact shaping of the roughly triangular tang - some are pretty blunt, others quite sharp. But if a file does have a clearly defined tang (rather than a "forged-in" metal handle as in the case of needle files for example, which we'll talk about later) then for your own safety you must always use a handle of some type - even for only just a quick couple of cleaning up strokes! Please, please, never use a file with just a bare tang pointing toward the under part of your hand/wrist, especially not if you've got the job mounted in the chuck of a drill or lathe!

And yes, I did quite recently see a very well-respected regular YouTube contributor talking about making a marking gauge. He was filing a small steel washer mounted in his pillar drill to make a circular "knife". He had the bare tang of the file pointing directly at the lower part of his wrist. IMO that's nothing short of being really stupid, and you don't need much imagination to guess just how much serious injury his hand and wrist would have suffered if that file had slipped or jammed - there's a major artery buried in somewhere in your wrist!

The picture shows several, both wood and plastic, including 3 wooden handles for Swiss & Needle files at the lower Left.

All types are freely available, both in wood and plastic, in many sizes and shapes, and in just about any tool shop. They're pretty cheap too - and much cheaper than surgery!

Decent wooden handles have a metal ferrule at the end with a quite small hole to allow the tapered tang to be driven into the handle. Personally I prefer the shape and the feel of wooden handles, but that's just a matter of personal choice, and I've got several plastic handles which I also use quite a lot.

The "approved" method for fitting and removing file handles (wooden and plastic) is as shown in the pictures. To fit, first use hand force only to push the handle onto the tang. Then grasp the body of file in one hand and strike the handle once (only) onto the bench (or in my case, onto the anvil section of the vice). This will produce a perfectly adequate fit.

To remove a handle, lay the file flat on the bench with the end of the handle overhanging the edge of the bench (or in my case, overhanging edge of anvil section of vice). Then, while grasping the file by the main body, but with the ferrule end of the handle some distance away from the edge of the bench/anvil, then pull the file smartly from L to R (I'm assuming right handed workers here - sorry lefties).

My own practice is to fit a handle as I select a particular file for a job, but when the job is finished I remove the handle and put both file and handle back in the drawer. Apart from anything else it's easier to store files safely without fixed handles.

Incidentally, the above fitting/removal methods shown are "approved" because A), it's the way I was taught; B), it works first time every time; C) it definitely won't damage either yourself or the tool!

But if you wish you can leave your handles permanently fitted. It's entirely up to you.

BTW, when fitting a new handle to a file for the first time, the method I was taught was to heat up the tang - NOT red hot but "pretty hot" (rather less for a new plastic handle I guess!) - and then just tap the handle into place by grasping the body of the file and simply striking the handle onto the bench, like the fitting method shown above. The heat apparently burns into the handle body and makes a strong permanent bond with the wood (and plastic)? I understand this is usually enough to do the job permanently.

As said, apart from files which came with pre-fitted handles, my own practice is to remove the handles after use, so sorry, I have little idea on what else works well if you want to permanently fit your own file handles.

Part 2 continues:

A while back Robbo 3, esteemed member of this fine congregation, PM'd me asking me to write something on files & filing. He'd noticed that I'd pontificated on this subject on the Forum before.

I was lucky enough to serve a "proper" engineering apprenticeship which started early 1961 (IMO "proper" means a good mix of practical - "workshops" - and theoretical - "schools" work), and like many others serving apprenticeships at the time, the initial practical part included quite a lot of basic bench work such as precision filing and hack sawing to quite fine limits (+/_ 0.001 in old money - i.e. a thou). This is/was called "fitting" in old terminology.

I've noticed that several other members here clearly also have good knowledge of the subject, but Robbo felt that some basics would be useful to members who perhaps have not had the "benefits" of such an apprenticeship (I wish I had had more appreciation of the in-depth treatment of these matters at the time - I just wanted to "get on with it" and start work with real aeroplanes - foolish boy that I was/am)! So I agreed to have a bash at writing up some basics which I hope members will find useful.

I also hope the following won't bore (or disagree too much with!) info that those already in the know have learnt in their own various past lives. And although it's long - very long actually - I've tried to make this a useful, practical guide for those whose main interest is woodworking but who need to do a bit of metal bashing now and then.

In the main I'll be dealing here with the common or garden "standard" metal work files and only talk about specials as the need arises.

Although they're as common as most other hand tools (more so than many?), files should be treated with respect, because they're really quite clever tools, and, in skilled hands, very capable tools too.

They're made of specially heat-treated high carbon steel (either full-cycle heat-treated, or case-hardened), and are therefore pretty hard (by most standards they're very hard). They have to be hard to allow them to happily cut just about any other metal of just about any other type or grade they're likely to come across.

But with this hardness comes a disadvantage - being hard means they're also quite brittle, which means it's quite easy to accidentally chip a cutting edge (a "tooth") - especially if allowing one file to bang against another.

Files are cutting tools, but unlike most other cutting tools, they have many cutting edges ("teeth"), as opposed to a chisel's or a plane's single cutting edge, or a router cutter's perhaps 4 cutting edges (max). But despite the many teeth, to work properly, all of the file's cutting edges need to be "all present and correct". To make it worse, being so hard, once damaged/blunted, the teeth are, for all practical purposes, impossible to re-sharpen.

So just as you wouldn't chuck a nicely sharpened chisel or a router cutter into your toolbox any old how, neither should your chuck files around - as above, be especially careful not to let files bang against each other.

These days files aren't exactly cheap (good ones aren't anyway), so I'll give a couple of ideas about safe storage further into this piece.

But all this means that if you value your tools at all, files should not be used to open paint tins, stir the contents thereof, nor for any other "gash jobs" that may come to mind - not even with a "rubbish file" from car boot sales and the like. And certainly not " 'cos it's only a file"!

So what are files for really?

Simply, files allow you to re-size, clean up, and/or re-shape pieces of metal of just about any type. And yes, I include all types of "normal" steel (including mild, stainless, spring, and silver steels); bronze; brass; copper; aluminium of all grades; nickel silver; cast and wrought iron; and even lead and solder, right on up to fancy stuff like titanium - not to mention many non-metals such as plastics of just about all types, bone, and, would you believe, wood too!

What's more, files allow you to remove material accurately, and to within fine limits - once you've acquired the necessary skill of hand!

I'll look at what acquiring that skill really means further on, but for now, jobs that might crop up in the shop and for which a file is the tool (unless you have metalworking machine tools such as lathe, mill, etc) can include:

:arrow: Removing points of screws & pins showing through visible surfaces of the work (wrong length chosen/correct size not in stock at the time!)

:arrow: Maintaining screw drivers (single slot type mainly, but a little re-work is also possible with Pozidrive & Phillips screwdrivers)

:arrow: Sharpening spade/flat bits; auger bits; Forstner bits; lip & spur bits; etc

:arrow: Sharpening various types of saw

:arrow: Removal of moulding "flash" from items with handles, etc, moulded either in plastic or die cast in metal

:arrow: General de-burring

:arrow: Making a router mounting plate (for a router table/stand)

:arrow: "Making" an adaptor to allow modern bits such as Torx to be fitted to old-fashioned tools like Yankee-type screwdrivers

:arrow: Unless there's a lot of "grinding" to do (for which I use a small circular stone in a Dremel tool with a special jig,) I also use a file for touching up the blades on garden tools such as a (rotary) lawn mower blade, shears, secateurs, etc. This is quick and easy, and is especially good for removing the burr/wire edge from the back of such blades

:arrow: General refurbishment, repair, and upgrade of tools and machinery

So files are pretty flexible tools in terms of what they can do and there are many other tasks we could add to that list.

Later on I'll look at some of the above tasks in detail, but first let's have a look at basic metalworking file types:

According to Wikipedia there's no internationally-agreed standard for the naming and classifying of files, but there are some terms which seem to be generally accepted in "general engineering English". But caution please, there are differences between US and UK usage, as well as differing usages and names within different trades on both sides of the pond. The following is what I learnt, and seems to line up pretty well with what I've heard others talking about. But as I've marked below, there are differences, particularly between US and UK terminology when defining file cuts/coarseness:

:arrow: LENGTH: Measured from the "toe" (opposite end to the handle) to the start of the handle (or where the handle is to be affixed - i.e. not including the handle itself, nor the softer, non-cutting and usually roughly triangular end called the "tang"). It seems that even in "mainland Europe", this measurement is in inches. Typically available off the shelf lengths are from 4 inches up to about 12 inches, in 2 inch steps, though I think there are some files available up to about 14, 16, or even 18 inches, and a few 3 inch files can be found too. Personally I find that some 4 and 6 inch files, plus some 8 and 10 inch files cover just about all I need for "standard" files. I have one 12 inch file, but then the work I do isn't normally all that big.

:arrow: "SHAPE" (CROSS-SECTION): The main shapes are flat, round, half-round, triangular, knife-edge, and square. These main shapes may also vary according to "sub-shape", meaning that for example a file can be parallel in both plan and in side views; or parallel in plan view but tapered in side view; or tapered in both plan and side views. And the taper can end either in a blunt-ish end or in a pretty sharp point.

Typical aspect ratios (length to width ratio) are around 10:1 for flat and half round files (i.e. a "standard" 10 inches long flat or half round file will be about 1 inch wide), with round, square, triangular files being about 20:1. Some "less standard" flat files have a much narrower length/width profile and these are called "pillar files". These are handy for getting into confined areas and I find having a couple of these useful but by no means essential.

In addition, some (but by no means all) flat files have a "belly" on one side, with one face being absolutely flat but the opposite face having a marked thickening in the centre of the cutting face (see sketch below, which I've deliberately exaggerated to show this feature). BTW, at the end of this piece I've given a few references which I found very useful. However, Reference 3, while giving generally excellent descriptions, does call the general body of the file a "belly", but that doesn't seem to refer to what I've shown in the sketch. I can't really say what is "right" or "wrong", but I was definitely taught what I've drawn below:

I find this bellied type of file very helpful for fast metal clearing, but from comments I've seen here and elsewhere, it seems bellies are now not so common on off the shelf "standard" flat files as they used to be.

:arrow: "CUT": This is where most confusion seems to arise.

It all starts simply enough, running thus (from coarsest to smoothest); mill or rough (mainly USA?); coarse (mainly UK?); middle cut (mainly USA?); ******* (both UK & USA); second cut (both UK & USA); smooth (both UK & USA); Xand dead smooth (both UK & USA). Not all of these cuts are freely available off the shelf, but this is not so important as in practice I think 3 cuts (say a mill, or a coarse, or a *******; then a second cut; and finally a smooth or dead smooth) will suffice for 99% of jobs. In fact I refer to my own files in my own "in-house terminology" as just coarse, medium, and smooth.

But as we'll see later, the coarseness of the cut can anyway be temporarily modified for specific purposes, and when we get to needle files we'll see different coarseness classifications.

The basic thing remember though is all these terms refer to the number of teeth per inch set out along the cutting face/s, and you'll soon get used to selecting the "right" cut to do a particular job efficiently, simply choosing by one of your files by eye, and by the cutting feeling you get when first starting the job.

I thought the picture below, which I copied from Wikipedia, was pretty good. If only all files were marked like that, it would make life much easier!

So far so good, but now it gets more confusing (and we're still only talking about "general metal work files" and not yet about specials)!

Most files have one set of teeth cut at an angle of about 25 to 30 degrees across a face, each row of teeth being parallel to the previous row, but with a second or double cut of parallel teeth superimposed on the first cut at a different angle (usually about 55 degrees), and usually somewhat shallower than the first set of teeth. This creates the common diamond pattern. Such files are called "cross-cut" or "double-cut" files (not "second cut" files, please note)! The purpose of that cross cut is to provide chip breakers. This increases efficiency and reduces the effort needed to remove the maximum material with each stroke of the file by ensuring that chips and burrs are cleared away from the teeth as quickly as possible.

OTOH, files with only one set of teeth cut into them are called "single-cut" files - "eezy-peezy rules OK"!

But do note, not all of the second ("cross-cut") teeth of some manufacturer's files are straight line tooth cuts at all - some are cut in a curved formation, doing away with the more common diamond pattern and creating a sort of "lazy S" pattern instead.

The next potential confusion arises from the fact that while, for example, a coarse grade file is considered by just about everyone to be pretty coarse (just as you'd expect). But for example, a 6 inch file classified as a coarse cut file will be a lot finer than, say, a 12 inch coarse cut file. This is because the manufacturer makes the depth and spacing of the rows of teeth of whatever cut being made proportional to the length of the file. Obvious really, because it's generally reckoned that you'll use big/long files on big work pieces, and little/short files on small jobs!

I hope the pictures make all these points a bit clearer.

Not all files have teeth cut into all faces. Some files come with one or even two faces without any teeth. These are called "safe edges" and make it easier to file one area of a job without an adjacent face of the file accidentally filing into an area of the job that you do not want to touch. BTW, one good way to judge the quality of a file is by its safe edges/s (if any) - cheaper files tend to leave the edges of the teeth "hanging over" onto the adjoining safe edge (see exaggerated sketch below), while better quality files have the safe edge/s ground off completely smooth after tooth cutting, giving truly safe edge/s. For special use you can of course grind your own full or partial safe edge/s by use of the off hand bench grinder, and you can touch up poorly-made files to improve safe edges in the same way.

Finally in the matter of cuts, half round and round files are made with a series of slightly overlapping flat cuts. Cheaper files have less of these cuts than those from the better manufacturers, so clearly the cheaper files do not follow the ideal circular or semi-circular profiles as well as the more expensive files. And cheaper half round files have "blunt-ish" sides (where the curved upper segment meets the flat under part). More expensive files which have nice sharp edges with teeth all the way down the curves, terminating in a sharp edge each side.

:arrow: And now, HANDLES: Some "standard" metal work files can be bought with handles permanently attached to the file (wooden or moulded plastic). Others come without handles, leaving the buyer to choose his own.

In the latter case, we're back to the above-mentioned "tang" again. In relation to the rest of the file, the tang is deliberately left pretty soft, and generally speaking, manufacturers are not all that careful about the exact shaping of the roughly triangular tang - some are pretty blunt, others quite sharp. But if a file does have a clearly defined tang (rather than a "forged-in" metal handle as in the case of needle files for example, which we'll talk about later) then for your own safety you must always use a handle of some type - even for only just a quick couple of cleaning up strokes! Please, please, never use a file with just a bare tang pointing toward the under part of your hand/wrist, especially not if you've got the job mounted in the chuck of a drill or lathe!

And yes, I did quite recently see a very well-respected regular YouTube contributor talking about making a marking gauge. He was filing a small steel washer mounted in his pillar drill to make a circular "knife". He had the bare tang of the file pointing directly at the lower part of his wrist. IMO that's nothing short of being really stupid, and you don't need much imagination to guess just how much serious injury his hand and wrist would have suffered if that file had slipped or jammed - there's a major artery buried in somewhere in your wrist!

The picture shows several, both wood and plastic, including 3 wooden handles for Swiss & Needle files at the lower Left.

All types are freely available, both in wood and plastic, in many sizes and shapes, and in just about any tool shop. They're pretty cheap too - and much cheaper than surgery!

Decent wooden handles have a metal ferrule at the end with a quite small hole to allow the tapered tang to be driven into the handle. Personally I prefer the shape and the feel of wooden handles, but that's just a matter of personal choice, and I've got several plastic handles which I also use quite a lot.

The "approved" method for fitting and removing file handles (wooden and plastic) is as shown in the pictures. To fit, first use hand force only to push the handle onto the tang. Then grasp the body of file in one hand and strike the handle once (only) onto the bench (or in my case, onto the anvil section of the vice). This will produce a perfectly adequate fit.

To remove a handle, lay the file flat on the bench with the end of the handle overhanging the edge of the bench (or in my case, overhanging edge of anvil section of vice). Then, while grasping the file by the main body, but with the ferrule end of the handle some distance away from the edge of the bench/anvil, then pull the file smartly from L to R (I'm assuming right handed workers here - sorry lefties).

My own practice is to fit a handle as I select a particular file for a job, but when the job is finished I remove the handle and put both file and handle back in the drawer. Apart from anything else it's easier to store files safely without fixed handles.

Incidentally, the above fitting/removal methods shown are "approved" because A), it's the way I was taught; B), it works first time every time; C) it definitely won't damage either yourself or the tool!

But if you wish you can leave your handles permanently fitted. It's entirely up to you.

BTW, when fitting a new handle to a file for the first time, the method I was taught was to heat up the tang - NOT red hot but "pretty hot" (rather less for a new plastic handle I guess!) - and then just tap the handle into place by grasping the body of the file and simply striking the handle onto the bench, like the fitting method shown above. The heat apparently burns into the handle body and makes a strong permanent bond with the wood (and plastic)? I understand this is usually enough to do the job permanently.

As said, apart from files which came with pre-fitted handles, my own practice is to remove the handles after use, so sorry, I have little idea on what else works well if you want to permanently fit your own file handles.

Part 2 continues:

Attachments

-

FF1 Belly-C.jpg197.5 KB

FF1 Belly-C.jpg197.5 KB -

FF2 Wiki-Files Flat-Smooth-2ndCut-*******.jpg110.8 KB

FF2 Wiki-Files Flat-Smooth-2ndCut-*******.jpg110.8 KB -

FF3 Single-Wavy-Double Cuts-C.jpg63.1 KB

FF3 Single-Wavy-Double Cuts-C.jpg63.1 KB -

FF4 ******* Cut-C.JPG64.6 KB

FF4 ******* Cut-C.JPG64.6 KB -

FF5 Safe Edge-C.jpg80.7 KB

FF5 Safe Edge-C.jpg80.7 KB -

FF6 Round-Half Round-C.jpg96.4 KB

FF6 Round-Half Round-C.jpg96.4 KB -

FF8 Fitting Handle-C.jpg82 KB

FF8 Fitting Handle-C.jpg82 KB -

FF7 Handles-C.jpg47.3 KB

FF7 Handles-C.jpg47.3 KB -

FF9 Removing Handle-C.jpg64.8 KB

FF9 Removing Handle-C.jpg64.8 KB