jimi43

Established Member

rxh":2f53vb8x said:Thanks for your kind comments Jim.

That's a very impressive piece of wood you have there - I bet it would be difficult to work. I have some mahogany from an old desk that might do but I haven't cut into it or planed it yet. I think mahogany should be stable as it was commonly used for making cameras and scientific instruments. I've also got some yew somewhere -it is pretty wild looking stuff but I don't know how stable it would be.

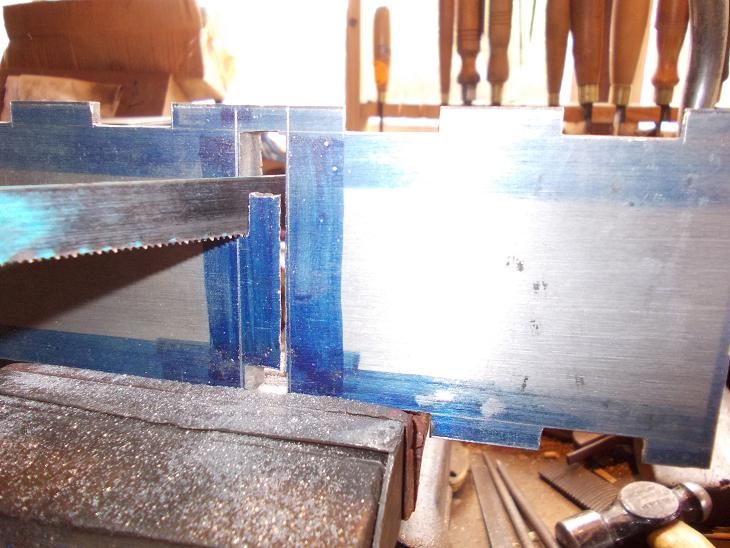

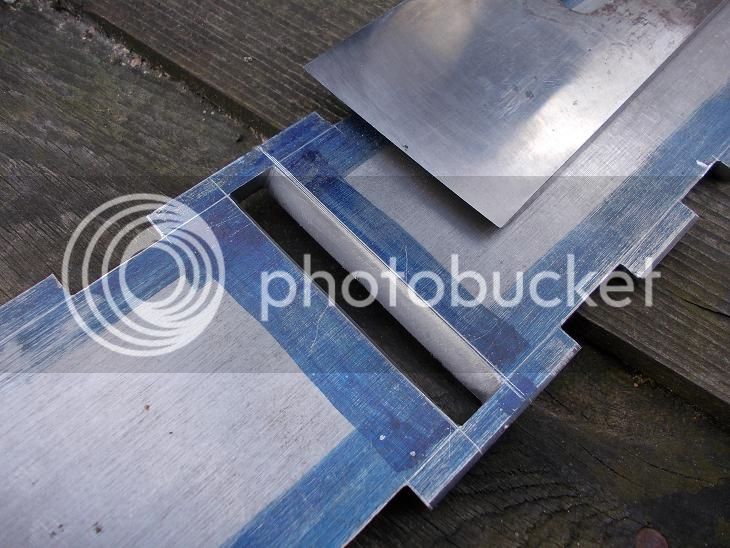

I've now made the frog block and cut out a rectangle that is intended to become the cap iron.

Mahogany was commonly used by user-made infill makers...but not considered the highest quality. Yew would be a nightmare because of the opposing grain...I love the wood but it is also fairly soft.

Rosewood (the real Brazilian Rio stuff) was the highest quality used...sometimes you find boxwood.

I think that the amount of time you are going to spend making the handle and infills...(and you will!)...I would get a nice exotic for it...check out Bill Carter's website for some examples!

Cheers and if you need any tips on the infill part let me know.

Jim